Munkres Introduction to Topology: Section 7 Problem 6

Part A

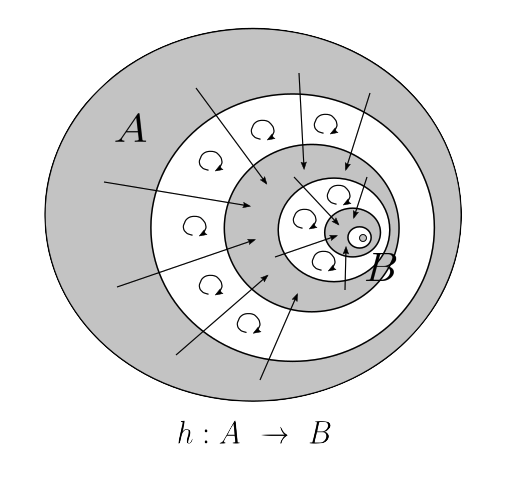

Given sets $A$ and $B$, with $B \ \subset \ A$, we wish to prove that if there is an injection

$f : A \ \rightarrow \ B$, then $A$ and $B$ have the same cardinality, meaning that there is

a bijection between them. Munkres gives us a lot of help in figuring out exactly

how to do this. We define $A_1 \ = \ A$ and $B_1 \ = \ B$. We then define recursive

formulas for $n \ > \ 1$, which is given by $A_n \ = \ f(A_{n \ - \ 1})$ and

$B_n \ = \ f(B_{n \ - \ 1})$. We assert that a bijection $h : A \ \rightarrow \ B$

is defined by:

$$h(x) \ = \ \begin{cases}

f(x) & \text{if} \ x \ \in \ A_n \ - \ B_n \ \text{for some} \ n \\

x & \text{otherwise}

\end{cases}$$

Next, we have to prove that $h$ is surjective. Let's pick some $x \ \in \ B$. Let's also assume that $x \ \not\in \ A_k \ - \ B_k$ for any $k$. Well, in this case, it follows that $h^{-1}(x) \ = \ x$, so for $x \ \in \ B$, we know that $x \ \in \ A$ is a point that maps to it.

Now, let's consider each set $A_k \ - \ B_k$, for all $k$. By the recursive definition, we have:

$$f(A_k \ - \ B_k) \ = \ f(A_k) \ - \ f(B_k) \ = \ A_{k + 1} \ - \ B_{k \ + \ 1}$$ This implies that $A \ - \ B \ \rightarrow \ A_2 \ - \ B_2$, then $A_2 \ - \ B_2 \ \rightarrow \ A_3 \ - \ B_3$, and so on, for all positive integers. Thus, for some $x \ \in A_n \ - \ B_n$, it is true that $x \ \in \ f(A_{n - 1} \ - \ B_{n \ - \ 1})$, meaning that $x \ \in \ B$ must be the image of some point $y \ \in \ A_{n \ - \ 1} \ - \ B_{n \ - \ 1} \ \subset \ A$. With both cases accounted for, we have proved that for any $x \ \in \ B$, there exists some point $y \ \in \ A$ such that $f(y) \ = \ x$. Thus, $h$ is surjective and injective, making it a bijection.

Part B